The English Premier League recently signed its biggest deal outside of the UK. Chinese electronics giant Suning has stumped up £560m for the television rights to broadcast its games to the growing legion of fans there. But it’s not just the size of the agreement that’s eye-catching. It’s a double display of soft power at work: by both China and the UK.

A number of Chinese businesses started frenetically investing in football after China’s president, Xi Jinping expressed a vision that his country should bid to stage the World Cup and then actually win it by 2050. This includes stakes in clubs such as Italy’s Inter Milan and Manchester City, sponsorship deals with FIFA, and big name transfers of players to Chinese clubs.

For the UK, football is becoming an increasingly important weapon in its soft power arsenal. With one of the most popular leagues in the world, the effects of international television coverage give a big boost to Britain’s reputation and influence abroad.

This is why Suning’s Premier League deal is especially significant: the record-breaking fee, the promise of better coverage, and the chance to engage a broader audience is good not only for the league itself but also for the British government.

Softly Does It

Harvard University academic Joseph Nye first used the term “soft power” to describe the way in which a country tries to get what it wants from other countries through an ability to appeal and attract. This contrasts with using hard power, synonymous with coercion or commanding others, to get what it wants.

Sport is a classic instrument of soft power. It enables a country to engage with the world, communicate a set of values it seeks to uphold, project an image it wants others to have of it and to gain access to resources and markets around the world.

China has long used football stadium diplomacy to secure access to natural resources around the world. Hence, the country’s latest foray into football is effectively an extension of existing policy rather than a radical new direction.

China has long used football stadium diplomacy to secure access to natural resources around the world. Hence, the country’s latest foray into football is effectively an extension of existing policy rather than a radical new direction.

And China is not alone in using football as a channel to globally exert its influence. Arguably, the most prominent exponent of football as an instrument of soft power is the UK, which consistently ranks highly in global soft power indexes.

The British government, via its cultural arm and main instrument of soft power, the British Council, already works with the Premier League through its Premier Skills programme. This uses football as a fun way of to gather people overseas and help them learn English. But football, and sport more generally, plays a much bigger role in terms of attracting investment into the UK.

The recent Sport is Great event hosted by the government in early November in Qatar was a perfect example of emphasising soft power through sport. It was billed “to promote the UK and Qatar’s shared commitment to delivering successful sporting events”. And it is no coincidence that the event was opened by Britain’s trade minister, Greg Hands, who was in Doha hot on the heels of international trade secretary Liam Fox.

It is part of an ongoing campaign of global engagement. During the summer, at the Olympic Games in Rio de Janeiro, Britain hosted a number of events under the “sport is great” moniker. The soft message of these events was that sport is a positive, uniting force that Britain is keen to be part of. Yet the harder, underpinning message was that, post-Brexit, Britain is newly open for business and needs to reset some of its trade and investment relationships.

Taking Advantage?

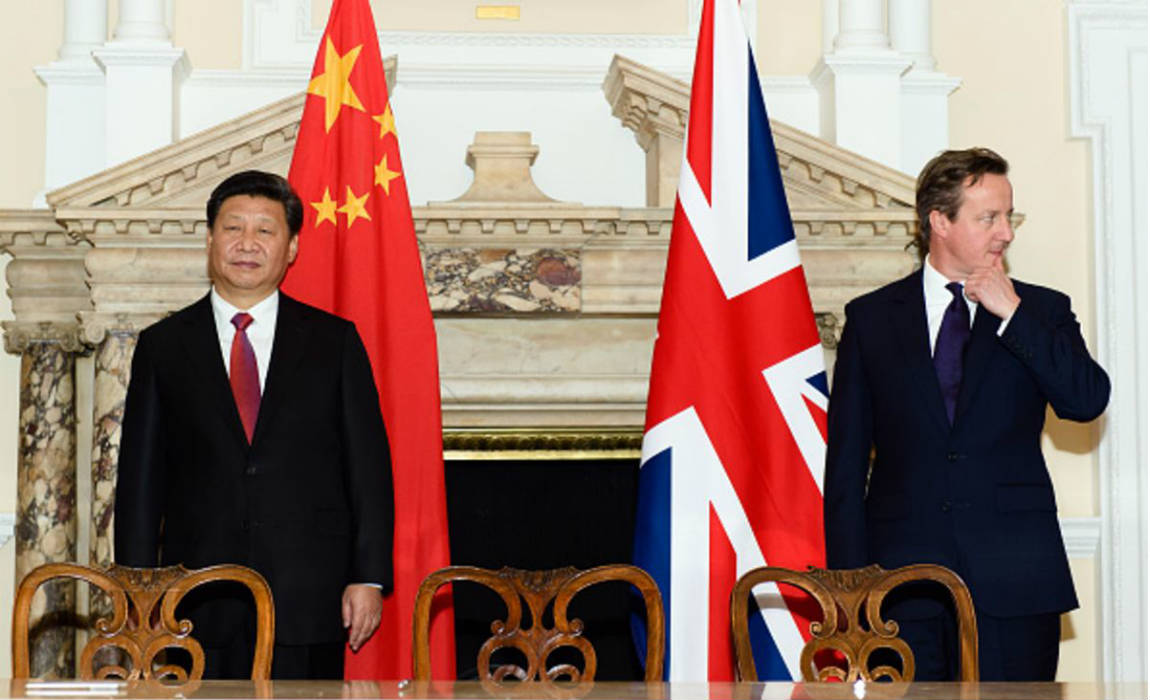

Although the DNA of Britain’s drive to exert soft power through sport dates back to colonial times, its more recent lineage can be linked directly to Tony Blair. The former prime minister saw football as a way to build business in countries like China, a view that was more recently enthusiastically adopted by David Cameron and George Osborne. Some people have even observed how Osborne actively courted the Chinese using football to entice its investors to spend in Britain.

One might be inclined to see current British government policy of soft power and sport to be obvious, smart thinking, and taking advantage of the competitive advantages the country possesses. The likes of the Premier League are a powerful, compelling proposition across the world and therefore constitute an important asset for Britain.

Some observers, however, criticise both the cynical nature of the way in which Britain is using its sport and the way in which the country seems to be prepared to compromise its supposed principles. One critic called Britain an “ethically challenged butler to Qatar’s World Cup dreams”.

Such a criticism is consistent with a more commonly held view that football has sold its soul for television money, sponsorships and overseas investment. To this list, we can probably now add geopolitics and soft power. But we shouldn’t be surprised, for that is what football has become. While China and Qatar have the pockets to grow their soft power, Britain and the Premier League are keeping apace by drawing on their experience and existing sporting power.

Such a criticism is consistent with a more commonly held view that football has sold its soul for television money, sponsorships and overseas investment. To this list, we can probably now add geopolitics and soft power. But we shouldn’t be surprised, for that is what football has become. While China and Qatar have the pockets to grow their soft power, Britain and the Premier League are keeping apace by drawing on their experience and existing sporting power.